Claudette Colvin died last Tuesday at age 86.

The actual date of her passage to ancestry is recorded as Jan. 13, 2026.

And while the date may not ‘remain in infamy’ as President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed the unforgettable tragedy of Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack, much should be said of Colvin’s bold stance against Jim Crow laws in Montgomery, Alabama, when she was a mere teenager.

That date was March 2, 1955.

Colvin was just 15 years old and a student at Booker T. Washington High School when she was ordered to surrender her seat to a white bus passenger.

As history records, nine months prior to the Civil Rights martyr, Rosa Parks, who ignored orders to do the same thing in order to accommodate white riders, Colvin had already demonstrated Black resistance.

According to widespread reports, Parks’ calculated action sparked the infamous 1955 Montgomery bus boycott.

For her bold action, she is acclaimed as the Mother of the Civil Rights Movement.

And while those facts are true, the undisputed truth maintains Colvin as the very first to defy Jim Crow rules by remaining seated on a segregated bus.

Fact is, while teenage Colvin might have frivolously disobeyed the law that day, Parks, a secretary of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was hand-picked to repeat the defiant act.

Parks herself admitted she had to be coerced into staging resistance.

However, eventually, to force attention to the issue, she agreed to the non-violent, passive resistance she had toiled daily to advance.

Parks was no pushover, though; in her quiet, humble manner, she publicly demonstrated Black power on Dec. 1955.

Along with rallying support from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his Southern Leadership Conference membership — to her credit, by her example, 40,000 Black folks sought alternative means of transportation, walking, taking taxis, or driving cars back and forth to work.

Their boycott crippled the business of white-owned bus companies.

And later, a judge ruled that segregation on buses was unconstitutional.

Notwithstanding, Colvin accepted the historical reference to the back seat.

“My mother told me to be quiet about what I did. She told me, ‘Let Rosa be the one.

White people aren’t going to bother her; her skin is lighter than yours, and they like her.'”

Believe it or not, during that era (and perhaps even now), the pervasive mentality was/is that fair-skinned citizens could be better trusted.

In choosing Parks, NAACP leaders also resigned themselves to the prevailing view that Parks had “good hair” and projected middle-class values, and therefore would better present a credible image that the public would likely align with.

That Colvin was handcuffed, removed from the bus, arrested, and tried in juvenile court seemed inconsequential.

She was charged with disturbing the peace, in violation of segregation laws, and battering and assaulting a police officer.

Predictably, the adolescent youth was convicted of all charges.

It should be restated that throughout the debacle that fated day, Colvin repeatedly stated constitutional rights she was taught in her segregated high school, which she assumed pertained to her.

Years afterwards, the trailblazer told audiences that, despite being denied recognition, she remained content knowing: “I made a personal statement.”

She explained that Parks didn’t and probably couldn’t dictate her own disdain for southern policies.

Without malice and admiration for Parks, Colvin regularly maintained respect for the movement that followed.

Her action should be regarded uniquely for its precedence — “mine was the first cry for justice and a loud one,” an adult Colvin said.

Another detractor to Civil Rights claims and early activism at the time of the historic event was her mother’s concern about repudiation because Colvin was pregnant.

She gave birth to a son, whom she named Raymond.

And while the federal court case resulted in the successful overturn of segregation in Alabama, Colvin was maligned, ridiculed, and branded a troublemaker in that state.

Eventually, with no advancement opportunities in her southern community, Colvin moved north to the Bronx to live with her older sister.

Here, Colvin became a nurse’s aide.

Reportedly, she worked at the same Manhattan facility for 35 years before retiring in 2004.

While living in the Big Apple, she birthed Randy, her second son.

Unfortunately, her firstborn, Raymond, died in 1993 of a heart attack.

However, Randy now lives in Atlanta, Georgia, and is father to the ancestors’ four grandchildren.

In tribute to her trailblazing act of resistance, the street Colvin lived on is named in her honor.

And in 2021, a mural honoring Colvin was unveiled along Claudette Colvin Drive in Montgomery, Alabama.

Colvin died while in hospice care in Texas on Jan. 13, 2026.

She passed away two days before the 97th anniversary of Dr. King’s birthday.

Colvin’s transition recalls the “Drum Major For Justice” sermon the preacher delivered in 1968.

Often resigned to downplaying his own self-importance

MLK eulogized himself by scripting a message about purposeful duty.

“If you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice; say that I was a drum major for peace; I was a drum major for righteousness.”

Colvin exemplified the sentiments he expressed.

Although many history books tend to omit her contributions to advancing the Civil Rights movement, the undisputed reality affirms the precedent she set as a student activist.

Indeed, Colvin was a drum major for justice.

While a resident of New York State, she vociferously stated opinions about life under Jim Crow rule.

On one occasion, she said, “I don’t think there’s room for many more icons,” the denied heroine said. “I think that history only has room enough for certain — you know, how many icons can you choose?”

Colvin expounded on that statement, saying:

“Most historians say Christopher Columbus discovered America, and it was already populated…they should say, for the European people, … that is their discovery of the new world.”

In 2026, it is written that Claudette Colvin was the first to sit in protest of racist, southern transportation rules. She paid a penalty for that action, but her effort was not in vain. Generations of grateful benefactors consider her an early drum major for justice.

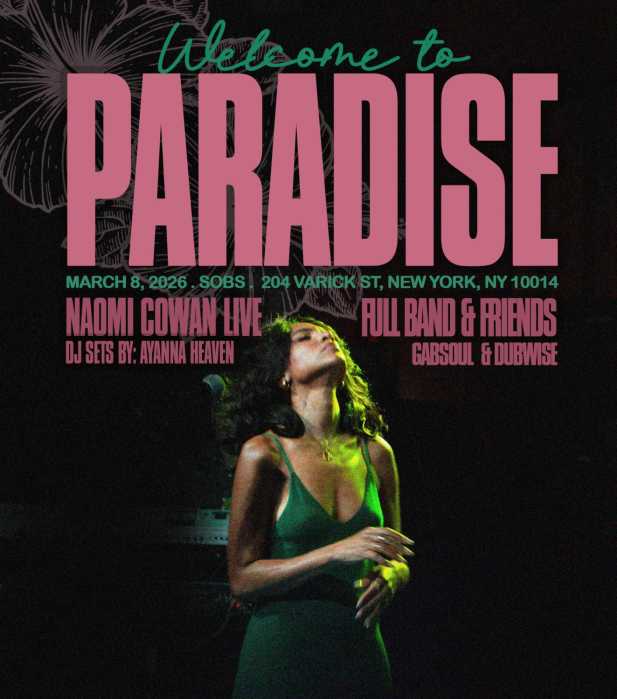

Grammy names Belafonte merit

“Ice Cream Man” is this year’s choice for the Harry Belafonte best song for social change award. Instituted in 2022 to honor the legend, the special merit award will be presented on Feb. 1 by the Recording Academy during the Grammy gala ceremony in California.

Written by four-time Grammy nominee Raye, the song speaks to the “social issues of our times and demonstrated and inspired positive global impact,” a committee designated to select the winner agreed.

In addition, they said the award represents “exceptional contributions to music and social advocacy,” which defines Belafonte’s legacy.

Previous winners include 2025 for “Deliver” a call for unity by Oman Jordan, Tam Jones and Ariel Loh; K’naan, Steve McEwan, and Gerald Eaton won in 2024 with “Refugee” which highlighted the plight of displaced people, and in 2023, “Baraye,” by Shervin Hajipour recorded an anthem about the plight of “woman, life and freedom” movement in Iran.

Catch You On the Inside!