Māhealani Uchiyama, who is of African descent, was born and raised in Washington, DC, during the last years of Jim Crow in the 1960s, which she felt was a fascinating place.

“We were subjected to segregation, yet it was an international city. Walking down any given street would expose you to multiple languages being spoken. When things did begin to open up, I was around people from all over the world. Yet, we were largely relegated to certain neighborhoods without access to swimming pools or playgrounds. Nonetheless, our community was vibrant,” she said.

Regarding family background, her maternal grandfather was from Kingston, Jamaica. Something that may surprise people about her is that she is in the process of researching it more, finding out that her earliest ancestors were brought to the US as early as the 1850s.

“My parents came from the deep South and were extremely entrepreneurial. At one point, they operated a nightclub on the ‘chitterling circuit,’ hosting some of the popular acts of the day,” she added.

Uchiyama sees her mother as the most significant influence on her path today as a musician and dancer because she was solely responsible for kindling and nurturing the artistic fire that motivates her.

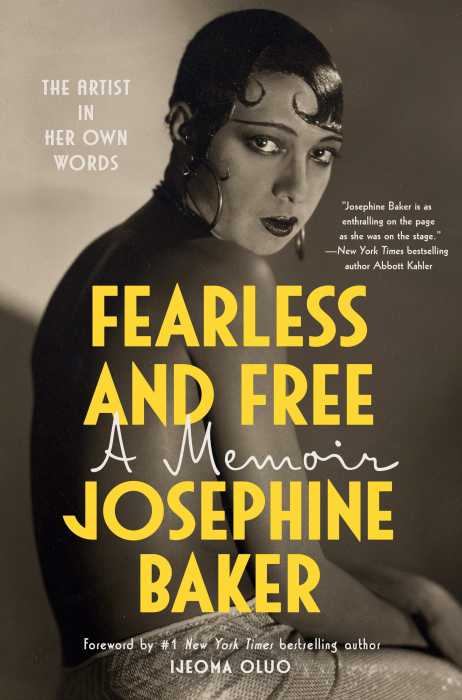

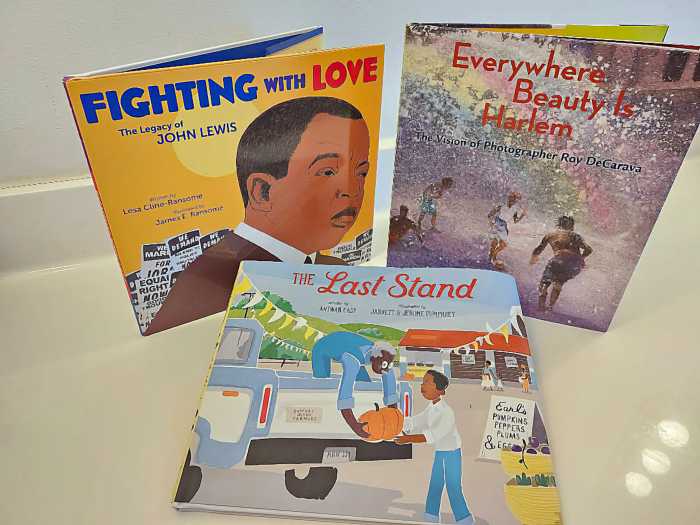

“Both of my parents kept a home filled with books and music. I grew up reading everything I could get my hands on, which gave me a sense of the larger world. There was also music always playing in the house. Mom saw to it that I continually had access to ballet and piano lessons throughout my growing years. At a time when such opportunities were rare, she was willing to let me travel 6,000 miles away from home to attend college in Hawaiʻi. It was there that my fascination with performance art became rooted,” she explained.

Her career started in the early 1980s when she taught hula (Hawaiian dance) and Tahitian dance classes after receiving permission from her teacher, Joseph Kahāʻulelio.

“Uncle Joe always played and sang our music live for our dance classes, so I began to do the same. Eventually, I was given the opportunity to make my first professional recording. Since that time until now, I have trained my dance company to sing as well as dance, and together with our wonderful musicians, we have toured throughout the Hawaiian Islands, Tahiti, New Zealand and California,” she shared.

As a result, she is now known as Hawaii’s first Black hula dance master.

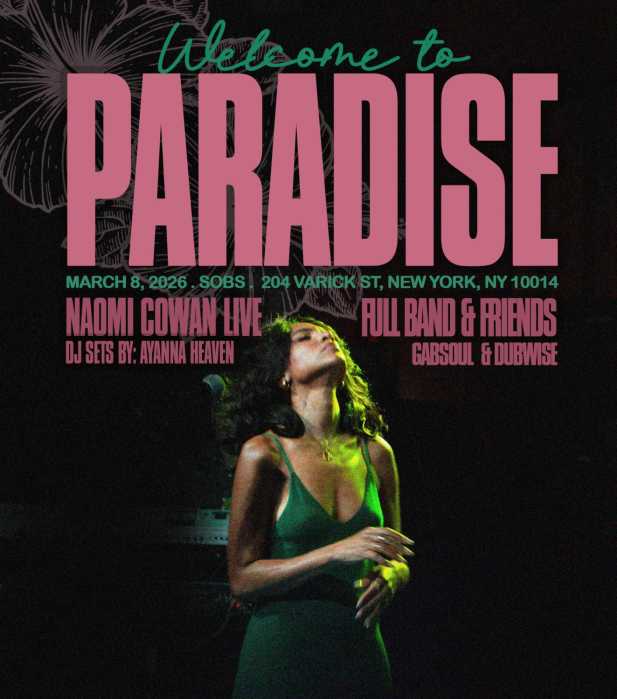

Uchiyama’s new song, “A Lei For Reverend King,” was released on May 1, Lei Day in Hawai’i.

She is working with her team to produce a new album, Pōpoloheno: Songs of Resilience and Joy, to be released on June 13.

She discussed what it has been like to write this song and work on this musical project, saying that the song came somewhat easily to her after being prompted by one of our project advisors, Adam Keawe Manolo-Camp.

“He mentioned that Reverend King had addressed the Hawaiʻi State Legislature in 1959. Hawaiʻi had just become a state, and there was no Capitol Building, so they met in the Throne Room of ʻIolani Palace. The Queen of Hawaiʻi had been removed from her throne and imprisoned, and the Kingdom was overthrown by outsiders. She offered words of comfort and hope to her people, and those words resonated with me in how they reflected Kingʻs words to his people. Thinking of all this, the melody and structure of the song just came very quickly,” she added.

One day, as a little girl growing up in DC, Uchiyama saw a photo of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Ebony Magazine. She described her immediate reaction and said, “My immediate response was something like, ‘Oh, that’s so pretty! I want to wear a necklace of flowers too!’ Of course, I was only about six years old at that time. I knew who King was but could not yet grasp what was happening in our country.”

In addition, she elaborated on how seeing the photo shaped the rest of her childhood and impacted her future. “The full meaning of that image was not understood until much later. What that image did do, however, was kindle an interest in Hawaiʻi. The more that I learned about Hawaiian culture and history, the more fascinated I became. By the time I was 11 years old, we were looking for hula lessons for me. Ultimately, this led to everything I am doing today,” she continued.

According to Uchiyama, this project celebrates the history of safety and solidarity found by formerly enslaved Black people who were initially welcomed in Hawaiʻi and seen as a valued part of the community.

However, in today’s era, Black people in Hawaii are often seen by many as perpetual outsiders who do not belong in the Hawaiian cultural dynamic. She also pointed out the many commonalities between Hawaiian and Black culture, including the respect of our ancestors, our relationship with nature, the misappropriation of our cultures, and our shared negative experiences (including extrajudicial killings, separation from ancestral lands, and more).

Uchiyama’s message, not only for the Black people in Hawaii but also the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander communities nationwide, is: “There is a bigger and longer history here than we have been given to understand. It is my hope that this project will produce a number of songs that will become a part of the conversation for Kanaka Maoli (Hawaiian) and African Americans who have more in common than we may know.”

She hopes to leave a legacy that reminds us as people that we belong to each other.

She also wants to inspire younger generations by teaching them that there is great beauty in every iteration of humanity, adding, “This beauty is often conveyed in music, dance, food and other forms of material cultural expressions. To engage freely requires mutual respect, curiosity, and humility. Music matters. Dance matters. We are not fully human in the absence of art.”

Interested people can listen to “A Lei For Reverend King” here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6WHEszD1G0.