As pop royalty Beyonce wrapped her six-night engagement in Tottenham, England, in Brooklyn, Nottingham-born British author John Masouri schooled New Yorkers on the impact of Jamaica’s home-grown music in the UK through the decades.

Although the time difference across the Pond did not correspond with daylight savings time on the East Coast, fans of both genres claimed the significant events brought “music to our ears.”

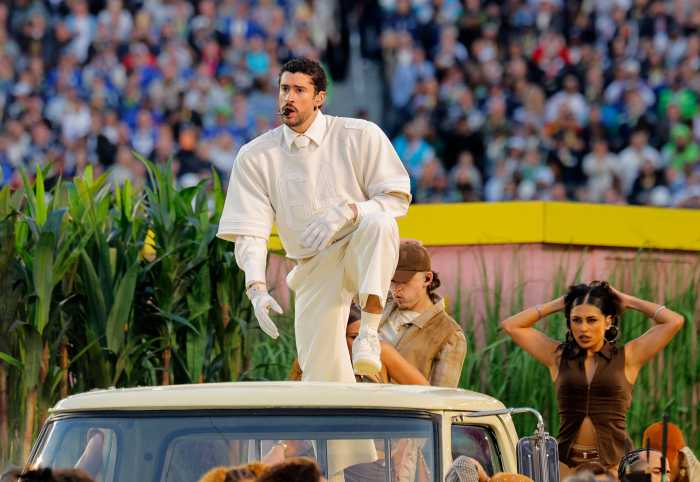

“Queen Bey is the best import we have had this year,” a group of concertgoers spokesperson said following the final engagement at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium.

“I don’t want to go home,” the celebrated pop star reportedly said last Tuesday before exiting the stage where her “Cowboy Carter” country tour of England ended.

And here, reggae aficionados described John Masouri’s one-night turnaround appearance at the Brooklyn Public Library as “enlightening and informative.”

Sonia Chin, one of the attentive guests, said the journalists provided edifying information about the music she loves.

“If the book was for sale here, I would definitely buy it,” she said.

NYPL restrictions prohibit book sales by authors.

The author stopped into the borough’s premiere archival location to promote his latest book, “Pressure Drop: Reggae in the Seventies.”

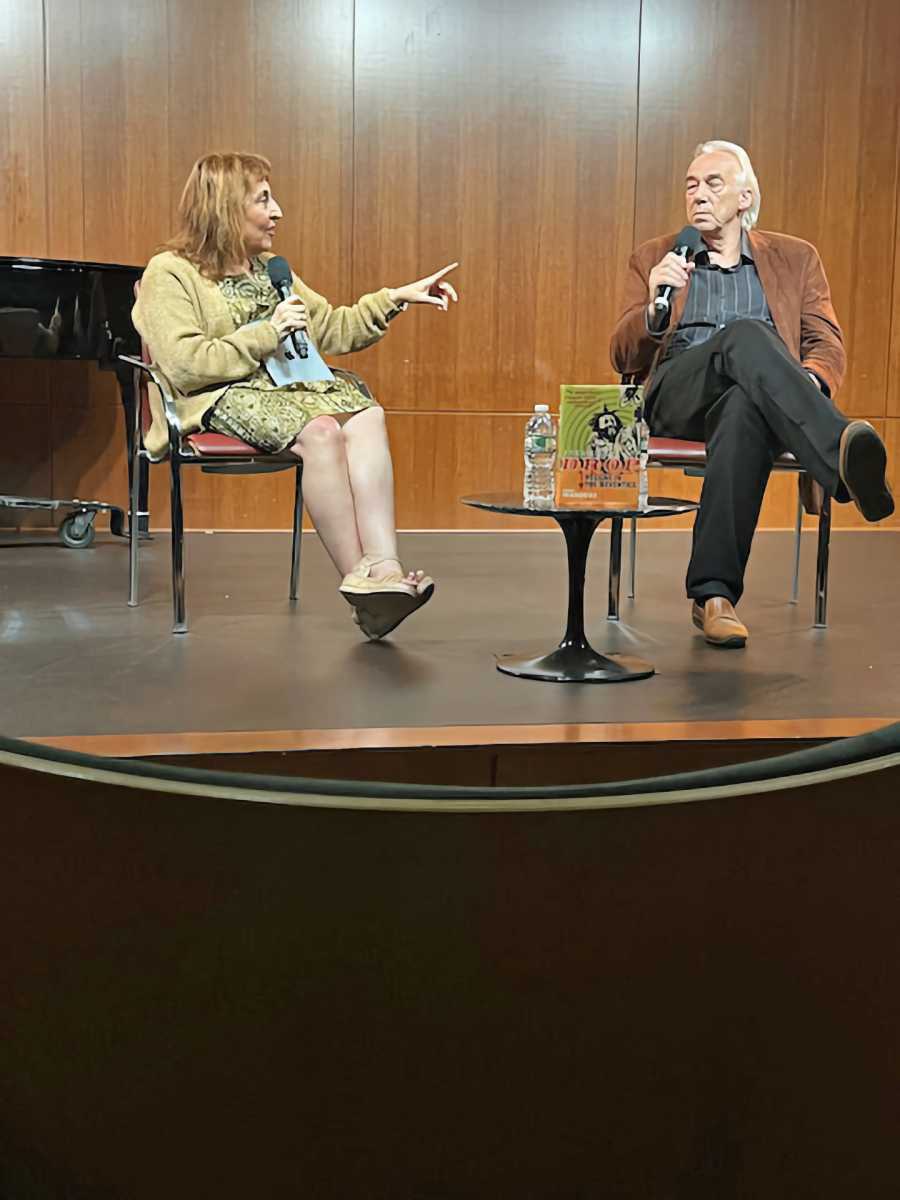

During a lively and informative two-hour discourse with Billboard Magazine’s Patricia Meschino, Masouri retraced the impact of reggae music on British culture then but delved further into chapters to opine on the genre’s impact throughout the last three decades of the 20th century.

According to the storyteller, the arrival of the intoxicating beat — borne in Jamaica — seemed to permeate youth culture in England.

He described the hard-driving beat as infectious. Masouri said the music infiltrated cultures, appealing to a diverse generation of trendsetters — encompassing radio playlists and the club circuit.

He detailed how recordings by Millie Small and Desmond Decker dominated the beginning years of the 1960s, which he said erupted across his shores.

Akin to a parallel contrasted by Motown Records here, Masouri cited how reggae ambassadors infused cultural appreciation, pride in heritage, and entertainment to the masses.

Their influence proved them to be the Caribbean innovators/diplomats at that juncture.

The way he described its emergence was that, personally, the genre competed for his attention, which challenged his own marriage.

One could interpret his description to mean, like a second love intrusion, reggae could have been perceived as a third-party intervenor.

Massouri chuckled at the reflective parallel he assigned but meant that when he first heard the rhymes and rhythm, he was consumed by the new musical distraction.

From early on, he fell in love with the beat.

One might access that the Empire Windrush vessel had docked more than immigrants with a shipload of trailblazing cargo.

More like a British invasion, Masouri described the then fad with contrasting parallels to the arrival here of The Beatles.

Apparently, while the music provided a pop alternative to British ears, reggae soothed the sensibilities of souls seeking spiritual consolation.

During a lively and engaging two-hour discourse with Billboard Magazine scribe Pat Meschino, the 37-year veteran reporter delivered a playlist with a discography that included liner notes on Burning Spear, Desmond Decker, Aston “Family Man” Barrett, Dennis Brown, Millie Small, Aswad, Steel Pulse, Jimmy Cliff etc who were all the rave during the 60s 70s and 80s. He hailed the pioneering contributions of toaster U-Roy, Winston Sparkes aka King Stitt, engineer Hopeton Overton Brown aka Scientist, singers Bob Andy and Marcia Griffith, Bronx-based label owner Lloyd Barnes aka Wackie, Cocoa Tea, and apportioned credits to Peter Tosh, Maxi Priest, Max Romeo and others with whom he shared cordial relationships.

“It was our culture (reggae). It was on the radio every day, we were growing up, and it was …just there.”

Things were different in America. Segregation was law in segments of society, and while Black music made inroads via Motown, Sun Records, and a few trailblazing labels, reggae never penetrated the charts. If not for college radio stations and later brokered outlets, reggae might have suffered prolonged suppression.

Undoubtedly, racism certainly inserted barriers to the progression of the Caribbean beat.

Masouri cited impediments overseas, too; according to the eye-witness, ultimately, after a surge, “racism killed the beat.”

He said hate groups such as the Skinheads protested any advancement of anything foreign or different, and SUS laws further hindered the semblance of dub, dancehall, or lover’s rock.

Eventually, the insurgency waned and dissipated.

Similar to stop-and-frisk provisions here, suspicious and suspect behavior permitted British police to detain individuals based on intuition.

Imagine Masouri, a Caucasian, hunkering and hankering in SUS-targeted locations. It must have been tenuous for whites to satiate their appetite for musical feasts.

Yet he persevered, venturing to blue beat spots in Brixton, Birmingham, and London.

History documents show that the reggae roots might have sprouted in 1948 when the Windrush ship sailed into British ports with imported aid from a diverse cargo of Caribbean optimists.

On arrival, immigrants discovered discrimination and, for more than a few, persecution.

Decades after the post-World War 2 importations, many realized they might have mistakenly envisioned a more receptive attitude from colonials, who were told they resided in the then-accepted motherland.

Undeniably, Masouri was in the minority at dark, dingy, underground night spots.

But he said that being poor, he did not conceive risk in partying with Indians and Jamaicans because, growing up in Nottingham, they were his neighbors.

The tales of Robin Hood and his Merry Men might have related.

Masouri also reported that for the 75th anniversary of the birth of reggae icon Gregory Isaacs, “Cool Ruler: The Musical” is now enjoying a successful theatrical run in London.

The unscripted information added that the actor now portraying the nicknamed Night Nurse character captures the essence of the deceased legend.

Reportedly, the play will stop in New York before wrapping in Jamaica later this year.

Another guest to listen to the reggae report included VP Records co-founder Pat Chin. She secured front seat vantage inside the Dweck Auditorium to tune in to the British report.

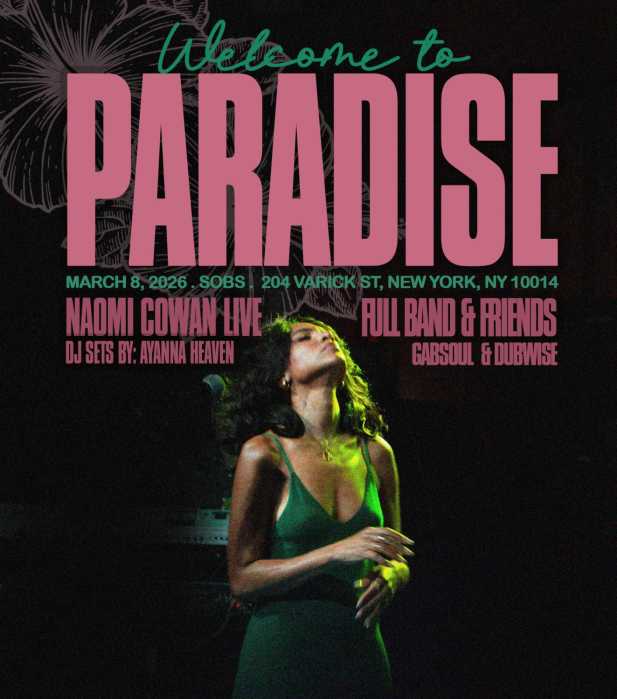

The revered biographer of “Miss Pat: My Reggae Music Journey” will be seated with Meshino on June 25 when the respected journalist gleans another poignancy perspective from a different location — Tropicalfete Cultural Landmark, 850 New York Ave. in Brooklyn.

The cultural presentations coincide with celebrations of Caribbean Heritage Month.

Catch You On the Inside!