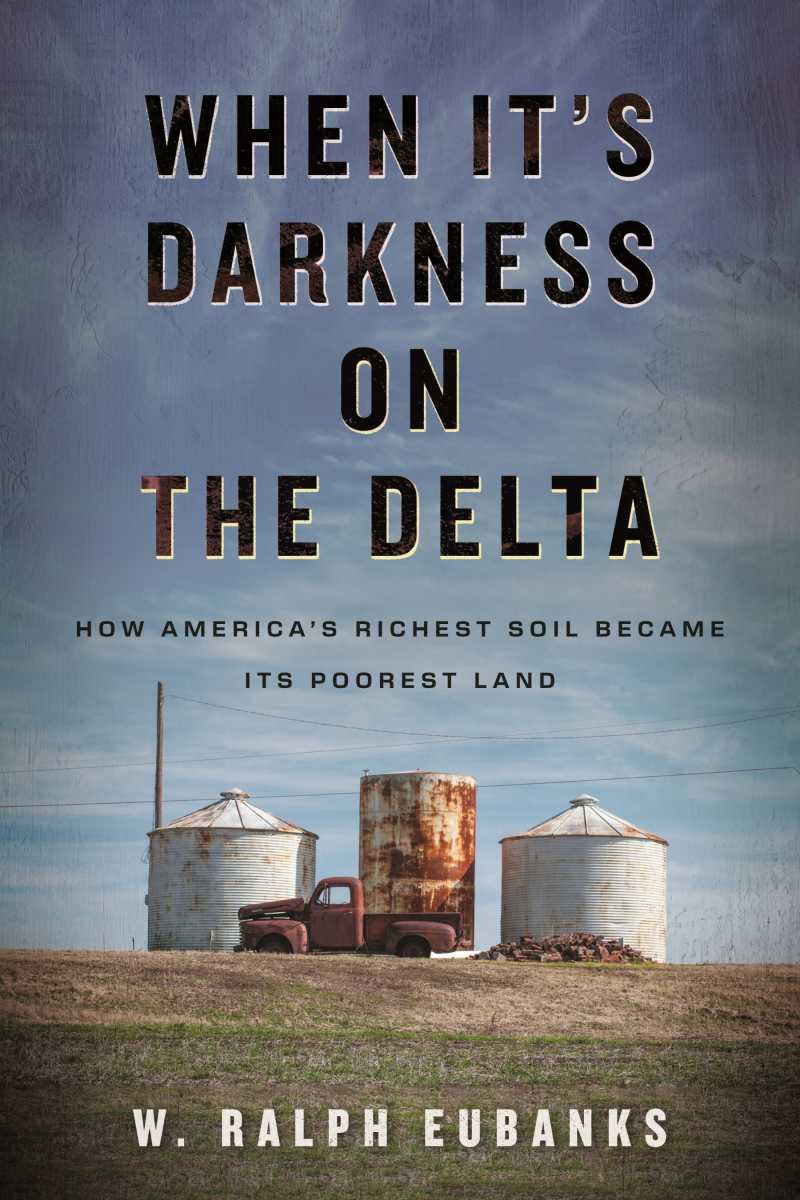

“When It’s Darkness on the Delta: How America’s Richest Soil Became its Poorest Land” by W. Ralph Eubanks

c.2025,

Beacon Press

$30.00

256 pages

Where you from?

That’s perhaps one of the first questions somebody might ask you because the answer tells them a lot. Where did you grow up? Where do you live now? What customs do you follow? Who are your people? Where are you from, and, as in the new book, “When It’s Darkness on the Delta” by W. Ralph Eubanks, what is that place like now?

When President Lyndon Johnson launched his War on Poverty in 1964, “the public face of [it]… was white” and Appalachian. “Black poverty in the Mississippi Delta mirrored” that which poor white Appalachians experienced, says Eubanks, but policymakers’ race influenced American perceptions of the “war” and, as often happens, little heed was paid to the Delta.

With just over 7,100 square miles of land bordered by bluffs and a river, the Delta “was firmly in the hands of the Choctaw Nation” in 1817, when Mississippi became a state. As settlers arrived, its soil became known for its fertility in growing crops, especially cotton. After Emancipation and Black flight to urban areas, Chinese and Italian sharecroppers were hired to work the land, but they didn’t stay; Black sharecroppers did, and during the Great Depression, Herbert Hoover promised to “divide the land of bankrupt planters into small Black-owned farms if he won the presidency.”

He did win, but he went back on his word. Instead, Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” fulfilled Hoover’s promise, ultimately creating Mileston Plantation, the state’s only “resettlement community” on which 110 Black families moved and farmed until the Great Depression hit full force and racism again became a factor in the then-present and future of the Delta.

On Providence Farm – founded by white “theologians and Christian missionaries” some forty miles from where Emmett Till was murdered – a desegregated hospital was established. White leaders helped Black farm workers organize into unions. The Box Project to combat hunger came from the Delta, and so did the blues. Everything changed there, and nothing has.

Poverty, says Eubanks, was born and still lies “buried deep in the Delta’s soil.”

And yet, there’s beauty, as evidenced in author W. Ralph Eubanks’ words, his memories, and the stories he tells. Every sentence in this book is fat with meaning and his love of the land he grew up near – but that can be a trap. Just know that you can’t race through “When It’s Darkness on the Delta.” No, it’s going to demand your time and your full attention.

Offer it, and you’ll see a wide, but microcosmic, view of racism and decay. Eubanks walked the Delta’s fields, looking for detritus of former farms; he drove past what’s left of homes and storefronts on a tour through his memories. He reveals Mississippi’s Delta through a historical lens and as a place ripe for the future, both of which will make readers understand why this biography of a place is important reading.

Just don’t rush it. Savor what you’ll find inside this book, and let yourself think about it. “When It’s Darkness on the Delta,” is worthwhile, no matter where you are from.