Caribbean and other African Diaspora people losing confidence in reparatory justice for over three centuries of slavery should take heart from the endurance of enslaved ancestors who persisted through the centuries without a sign that emancipation will come.

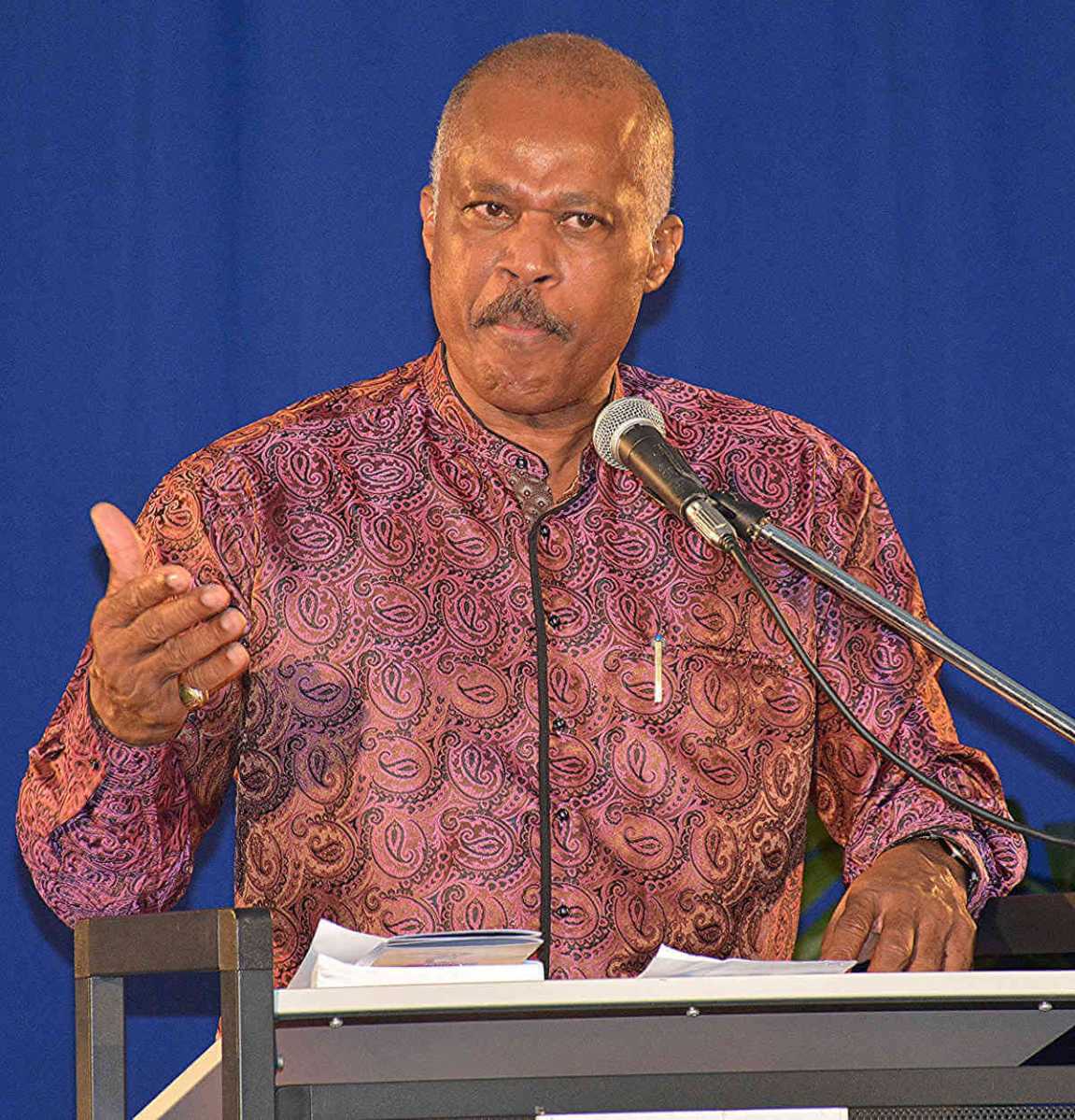

University of the West Indies Vice-Chancellor, Hilary Beckles, recently used examples of a likely hopeless state of mind of the enslaved, a little more than a decade before abolition of British slavery in 1833 and emancipation in 1838, who got liberation from an era that reached back to the early 16th Century.

“After 300 years of slavery, do you believe that your ancestors in 1820 thought they would ever see freedom… If you have been a slave for 300-400 years do you believe that anyone in that world could imagine freedom?” he asked rhetorically.

The professor then surmised, “if you had done a survey in 1820 among all the enslaved people of the Caribbean [asking]: ‘do you think freedom will come in your lifetime?’”

“I would venture to say that 90 percent of them would say ‘no, we will not see freedom in our lifetime.’

“But they did.”

This was the summary of Beckles’ plea for the African Diaspora to hold the faith and stay the course in pressing American and European governments that legalised slavery to repay — not necessarily in cash but through tangible developmental assistance for the centuries of forced labor that produced much of the wealth the modern world now enjoys, but for which the laborers were never compensated.

The renowned historian who has authored more than 21 books, including 17 on slavery and its effects on Third World societies and economies, likened the press for reparations to the manner in which Africans built pyramids block by block over the centuries, passing the task on to the next generation.

He said the current push for reparations is the third iteration with the first being the collective instances over the hundreds of years whenever a slave was freed for whatever reason, that person sought payment for enslavement.

This request was of course refused, similarly was the request of slaves during discussions on emancipation, the second iteration.

The third iteration, he said, began with demands of Jamaican visionary Marcus Garvey and continues to this day.

“Something is going to happen in our lifetime that will trigger this conversation, because it is now taking place all over the world.

“The world is coming around to the realisation that a small number of people on the planet, the Europeans, used their military superiority to march into the continents of the world, destroy the societies and economies.”

“Emancipation without compensation, to them, was an injustice,” Beckles asserted

Zeroing-in on but one example of unpaid forced labour for which the descendants of those who survived that era are now demanding compensation, Beckles cited the Emancipation Act, “the most racist Act ever passed in the British Parliament … It was the most vile and vicious legislation ever passed.”

He pointed out that in justifying slavery, the enslaved were considered property and not humans.

“So, the Emancipation Act is predicated on the assumption that the 600,000 black folks in the Caribbean were not human beings.

“They were property, therefore we [British government] were going to pay property compensation to the owners of the property.

“This is why the Act is racist because it never affirmed the humanity of the African people. It confirmed their property status as a precondition for emancipation.”

In the British parliamentary deliberations on the Emancipation Act the value of the labour of the slaves to be emancipated was calculated at 47 million British pounds.

The British government was however unable to pay that amount of money because it represented more than 50 percent of that country’s gross national income, Beckles pointed out.

In the face of slave owners’ demands for their full payment, a compromise was reached that saw them getting 20 million pounds [15 billion pounds in today’s value] cash.

Incidentally, the British government took out a loan to make this payment and finished repaying that loan only in 2015.

“It merely tells you how enormous this thing was,” Beckles said.

There was still the matter of the other 27 million pounds owed to the slave owners in 1833.

Through the Emancipation Act, the British Parliament decided that despite slavery was being abolished, the slaves were to be made to work for an addition six years giving the owners additional free labour under a scheme called ‘Apprenticeship.’

“If you’re giving 20 million pounds in cash and our ancestors had to work off the 27 million pounds, clearly by the irrefutable laws of mathematics the enslaved paid more for their freedom than the British government.

“We paid reparations after we were free for our own freedom,” Beckles observed.