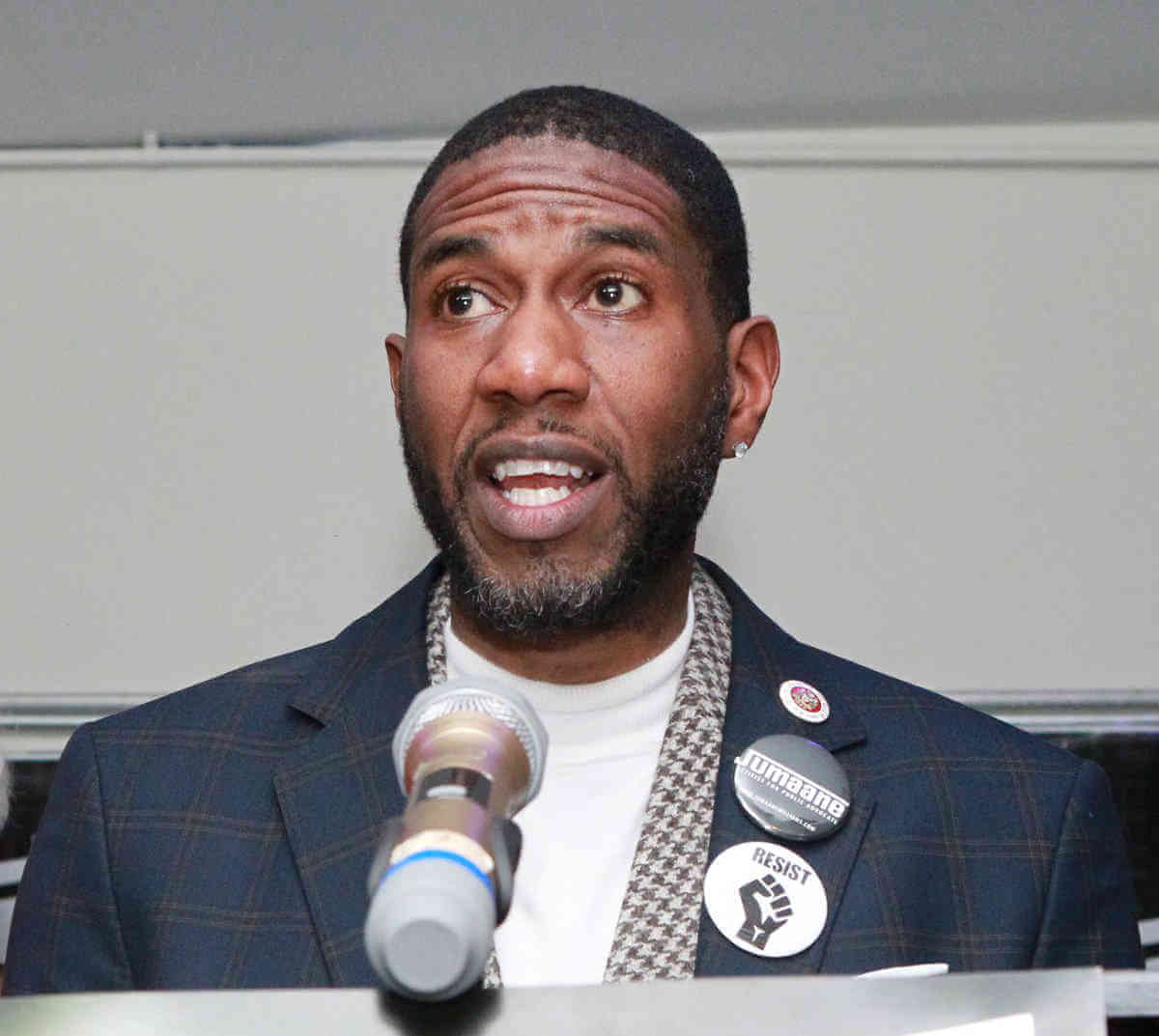

New York City’s public advocate

The recent rise in hate crimes and anti-Semitic attacks in our city and our state are a stark reminder that the human condition is ever a work in progress. It is in moments like these that our society must commit to work even harder to find common ground and provide a space for healing and honest conversations.

I believe part of those conversations must include revisiting our history so it can serve as a lesson for the future. In this moment, I think about a small sliver of blocks in Manhattan in particular.

It’s called Freedom Place — a stretch of city pavement from 66th to 70th Sts. off West End Ave. that was dedicated over 50 years ago to the memories of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman. Three civil rights workers — one black and two Jewish men brutally murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Philadelphia, Mississippi on the night of June 21, 1964. Their deaths helped spark the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

As time has passed, many New Yorkers may not remember who Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman are. They, like the civil rights age, belong to old black and white videos from a bygone time. But a quick search will reveal the infamous and gut-wrenching photo of Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman at the top of the page. They are lying dead in a shallow grave, shot to death through the heart. Looking at that photo of the three men lying face down in the dirt, it’s pretty hard to tell the difference between them.

The point of raising the memory of these three isn’t to romanticize African-American-Jewish relations, but to point out that in various points in our mutual histories, the two communities have worked together to address societal ills. That we must raise our collective voices together not only to condemn instances of anti-Semitism and racism, but create meaningful platforms to have dialogue about the underlying causes of these incidents. Knee-jerk reactions to score political points while funding some causes and not others really doesn’t help solve the problem in the long-term.

Seven years ago, as members of the City Council, my colleague David Greenfield and I co-sponsored a trip for a multi-racial group of students from Yeshivah of Flatbush and Brooklyn College Academy to commemorate Holocaust Remembrance Month. The students spent the morning at the Museum of Jewish Heritage learning about the mass murder of Jewish people during World War II, then traveled together that afternoon to the African Burial Ground National Monument to learn about the atrocities committed against African slaves and their descendants. In between, we hosted the students for lunch at City Hall, where they had an illuminating discussion about stereotypes, genocide and the importance of diversity.

It has been my belief that these conversations need to happen not only amongst our youth — who continuously need to be educated about our shared histories — but between adults as well. Four years ago, Councilman Brad Lander and I co-hosted a racial justice town hall at Congregation Beth Elohim in Park Slope. Moderated by the Brooklyn Movement Center and Showing Up for Racial Justice, the forum fostered an honest conversation about interpersonal racism and privilege in our society.

We can’t hope to break the cycle of hate that fosters these incidents unless we are willing to have uncomfortable discussions about the economic and social ills behind them. We have to deal with the truth if we are to have reconciliation.

This week, as we celebrate the memory and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, I would ask all my fellow New Yorkers to look beyond slogans and look to have a conversation with someone from another community outside their own — to engage someone you wouldn’t normally talk to. King and his legacy are too often sanitized. His was a revolutionary spirit, and the civil rights movement was revolution that brought together fighters from different backgrounds and communities, like Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman, toward common purpose. We should carry forward with that same revolutionary unity. Maybe in those small conversations, at the water cooler or on the subway, discussing the crazy weather or our beloved Knicks, we can become comfortable enough to begin to have larger conversations.

Freedom Place is a stretch of four New York City blocks in a neighborhood where most New Yorkers couldn’t afford to live. It is ironically hidden in the shadow of some buildings once named after Donald Trump, a quiet, ordinary street commemorating the memory of three young men who lost their lives to hate and intolerance in a fight against the same.

I’d imagine it would be the kind of block where in a different time and place Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman might sit and have a conversation. They might talk about love, sports or politics. They might talk about racial injustice and voting rights.

My sincere hope is that our generation finds Freedom Place. And has a conversation when we get there.