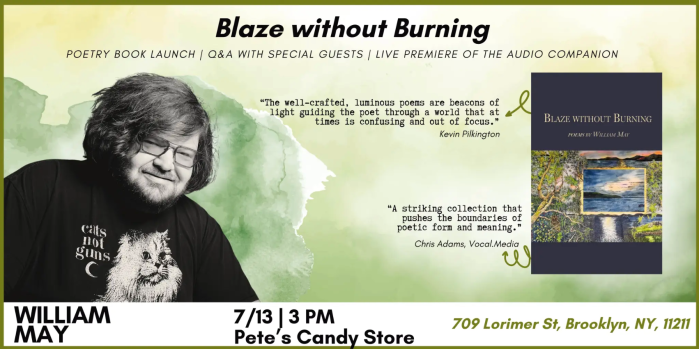

FREEPORT, Trinidad and Tobago, May 22, 2014 (IPS) – Erle Rahaman-Noronha is not a revolutionary, not in any radical sense at least. He is not even that exciting. In truth, Rahaman-Noronha is merely a man with a shovel, a small farm, and a big dream. But that dream is poised to conquer the Caribbean.

Rahaman-Noronha wants to see ‘permaculture’ – short for permanent agriculture – take root and spreads across the Caribbean, and he is doing his part by teaching anyone who will listen about its benefits.

Joining him is a fluid group of permaculturalists working from their home islands and sharing the same goal: to harness permaculture as a solution to climate change, food and water insecurity, and rising costs of living.

“Here, this is the Bible,” Rahaman-Noronha tells IPS, laying a book on the table. Behind him, orange trees rustle in the wind, the sharp smell of Trinidadian cooking wafts out an open window, and white-faced capuchin monkeys screech in the distance. The cover reads, ‘Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual’, and the contents offer surprisingly simple solutions to modern problems through economically and environmentally sustainable living.

Author of the manual, Australian Bill Mollison, first used the term nearly four decades ago and since then the idea has spread to Europe and the U.S. Now, the developing Caribbean is beginning to embrace the philosophy of permaculture, especially since 2008’s global recession.

Born in Kenya, Rahaman-Noronha – whose work was recently highlighted in a TEDx talk – fulfilled a keen interest in the environment by studying applied biochemstry and zoology in Canada.

“I’ve always had a strong passion for the outdoors and conservation, but just doing conservation doesn’t make money,” he says with a chuckle. “Permaculture allows me to live on a site, produce food on a site, produce an income, as well as practice conservation.”

Wa Samaki is Rahaman-Noronha’s permaculture farm, and it has been his workplace, classroom, grocery store, and home since he relocated to Trinidad in 1998. Meaning “of the fish” in Swahili, Wa Samaki covers 30 acres in Freeport in central Trinidad.

Although he uses no fertilisers, herbicides, or pesticides, Rahaman-Noronha is able to make a living off the farm’s fruit, flower, lumber, and fish sales. His newest addition is a large aquaponics system, a closed loop food production system in which fish tanks and potted plants circulate water and sustain one another.

With his partner John Stollmeyer, Rahaman-Noronha works to spread awareness of permaculture across the Caribbean, home to nearly 40 million people who are particularly susceptible to climate change.

The pair consults Trinidadian businesses, teaches permaculture design courses (PDCs), and holds workshops everywhere from Puerto Rico to St. Lucia. “How are we going to create sustainable human culture?” Stollmeyer asks. “Discovering permaculture for me was a wake up call.”

WHERE ENVIRONMENTALISM MEETS SAVVY ECONOMICS

The need for conservation is in no small part a result of climate change, especially when the Hurricane Belt covers nearly all of the Caribbean.

Trinidad and Tobago continues to compound the issue as both a major exporter and consumer of fossil fuels. The country produced more than 119,000 barrels of oil per day in 2012 and 1.4 trillion cubic feet of natural gas that same year, all the while boasting the second highest rate of CO2 emissions per capita in the world, more than twice that of the United States.

United Nations data dating back to 2005, the last time such statistics were compiled, indicates that industrialised agriculture accounts for 20 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in Latin America and the Caribbean.

In this environment, Rahaman-Noronha’s goal is to become an incubator of conservation start-ups that cannot secure necessary bank loans. Currently, he houses beekeepers and a wildlife rescue center on the farm for minimal rent, and he hopes that list will grow.

One such entrepreneurial mind that passed through Wa Samaki was Berber van Beek, a native of Curaçao who recently moved home after years of wandering the world. Before returning to the Caribbean, she practiced permaculture across Europe and Australia, but when van Beek wanted to develop her skills in a tropical climate, she came to Rahaman-Noronha.

“He gave me a lot of freedom on his farm to make and create a design,” van Beek says, describing a garden of banana trees she planted at Wa Samaki.

In Curaçao, van Beek uses permaculture as more than simply a food source. She realises its social potential and is working to start after-school programmes for at-risk youth who can learn useful gardening skills and the responsibility and respect for nature that come with caring for their own gardens.

In addition, she is soon opening her first large-scale organic gardening class, closely resembling a PDC.

Such initiatives are urgently needed in Curaçao, which is facing a stagnant economy and is currently nursing a youth unemployment rate of 37 percent.

According to van Beek, shifting global climates and markets have major effects on her own island in which nearly everything must be imported. “If you go to the supermarket, look where your food is coming from. Is it coming from Venezuela or is it coming from the U.S. or is it coming from Europe?” she says. “People could be more aware of what to buy and what not to buy.”

The problem, experts say, is regional. According to the Food Export Association of the Midwest USA – a group of nonprofits focusing on agricultural issues – around 80 percent of food consumed in the Caribbean is imported.

The beauty and purpose of permaculture is that it is a system of solutions that can be practiced at any level to combat environmental issues.

“You can start in your backyard, so there’s no cost. You can implement certain parts of it in your apartment if you really need to,” Rahaman-Noronha explains. “If you have a porch with some sunlight, you can plant something there and start thinking about permaculture.”

Naturally, van Beek took his message to heart, keeping a perfectly groomed permaculture garden in her own tiny backyard, using dead leaves as fertiliser and recycled rain and shower-water to sustain the plants.

“Seeing is believing,” she says. It’s her own quiet mantra, spoken when she describes her approach to spreading permaculture, and vocalised when she needs the energy to keep pressing on and to convince others that this is the right path.

Rahaman-Noronha, too, has worked to convert non-believers. From schools who tour the wildlife center and his farm to the several thousand people who watched his TEDx talk online, he is adamant that he has traded in misconceptions for progress.

“I think [the reason] I don’t get challenged…is that I’m not just preaching permaculture,” he says. “I’m actually practicing it.”