Community organizers across the country discussed ways to protect communities against threats to mutual aid and solidarity efforts, during a virtual conversation moderated by Dean Spade, author of Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the next) [2020]. It was co-sponsored by Haymarket Books and the Community Justice Exchange (CJE).

Spade began the conversation, sharing how the myth of mutual aid often comes from government, corporate media and the elite, with limited participation from local people in a community. He also shared what it means to him, as a theory of transformative change.

“The reality is that social change happens when huge numbers of ordinary people organize to fight back, and to disrupt what’s happening and to make it impossible for the violence to continue. Injustice is not a result of misunderstanding, but instead it is a result of domination,” said Spade.

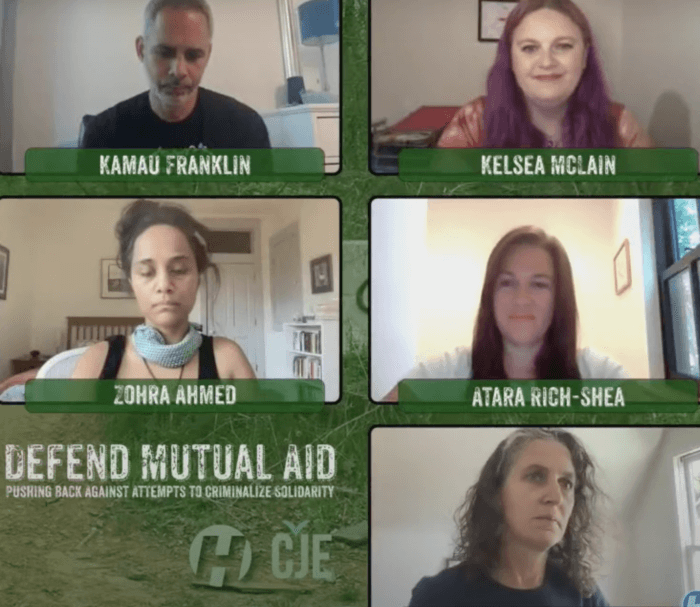

Speakers during the conversation were Kamau Franklin, Zohra Ahmed, Atara Rich-Shea and Kelsea McLain.

Franklin is the founder of Community Movement Builders (CMB), and Ahmed is an assistant professor of law at the University of Georgia School of Law. Rich-Shea is a regional organizer at the National Bail Fund Network (under CJE), and McLain is the deputy director of the Yellowhammer Fund.

In his remarks, Franklin shared that many organizations have been involved in some kind of mutual aid work, which was extended when they started doing work against Cop City in Atlanta. “To be clear — cop city is not just a controversial training center. It is a war base where police will learn military-like maneuvers to kill black people and control our bodies and movements,” said Kwame Olufemi, a CMB member.

McLain discussed how the attacks on abortion rights and reproductive freedom in Alabama led the Yellowhammer Fund to create an abortion fund, as part of its mutual aid efforts.

“Our work became very significant and important as our abortion fund grew, because we were able to serve more people. So we were happily providing abortion care, funding for abortion care, even under all of these bans and restrictions, up until the Dobbs decision (Supreme Court, June 2022),” she said.

“We expected our work was going to look more like the practical support side of our work, which means that we were caring for the needs outside of just the funding for the abortion, which is huge,” she added.

In addition, Rich-Shea discussed how the criminalization of mutual aid actually attacks a movement and the work to build a better world.

“It looks like right-wing media attacks (doxxing or threats of violence by individuals and also the media), government investigation, and then legislative strategies to increase the criminalization of mutual aid through criminalizing or regulating acts of solidarity and protest,” she stated.

Criminalizing mutual aid, said Rich-Shea, “limits our ability to actually do our community care work. It has a chilling effect on funders and allies. It isolates the people who need help the most, from movement comrades and resources, and it instills fear and anxiety in activists, comrades, and allies, which is intentional. This isn’t accidental. It’s an intentional counterinsurgency action to isolate us from each other.”

Ahmed discussed the legal strategy that the Attorney General in Georgia has put forward in the case against the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, to highlight how the State put the case together, how it uses the law to intimidate, how it uses jails to intimidate, and to think about how to respond.

“So in the preliminary hearing of the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, and in all of the preliminary hearings and bond hearings, the district attorney starts with these really magnificently broad characterizations of facts, and at no point in these really broad descriptions of things that go back three, four years, do they mention a single person’s name,” she said.

They start with “no real specific allegations of fact connected to an individual, sort of the building blocks of criminal law, none of that, just broad characterizations,” she added.

The discussion ended with Pilar Weiss, founder and director of CJE, who shared ways to protect people, when it comes to making decisions to support mutual aid campaigns.

“One is centering who is most at risk. Another area folks can really think about as an offering to protect each other is making sure we always keep our fundraising disclaimer language clear and updated (non-criminalizing).”

To support the work of Haymarket Books, those who are interested can donate via Paypal. Those who are interested can find all purchase options for Spade’s 2020 book here.