PORT-AU-PRINCE, June 19, 2013 (Haiti Grassroots Watch) – Three years after its star-studded launch by President René Préval, actor Sean Penn and other Haitian and foreign dignitaries, the model “Corail-Cesselesse” camp for Haiti’s 2010 earthquake victims has helped give birth to what might become the country’s most expansive – and most expensive – slum.

Known collectively as “Canaan”, “Jerusalem” and “ONAville”, the new shantytown spread across 1,100-hectares is here to stay, Haitian officials told Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW). Taxpayers and foreign donors will likely spend hundreds of millions to urbanise the region and as much as another 64 million U.S. dollars to pay off landowners, who are threatening to sue the government and humanitarian agencies.

Three years after its launch, the multimillion-dollar model camp located 18 kilometres northeast of the capital of Port-au-Prince is today surrounded by tens of thousands of squatters’ shacks and homes that have become a source of embarrassment for local and international actors alike.

Before the earthquake, most of this arid, rocky expanse running from the outskirts of Port-au-Prince up to Cabaret was largely empty. Much of it is owned by the Haitian firm NABATEC S.A, which since 1999 had tried to develop it into an “integrated economic zone” (IEZ) called “Habitat Haïti 2020″.

The Habitat Haiti 2020 plan included industrial parks, single- and multi-unit housing for various income levels, schools, green spaces and a shopping mall. A Korean company and a U.S.-based humanitarian group had already purchased land within its perimeter, and on the eve of the quake, NABATEC was holding discussions with a number of foreign firms interested in setting up factories and was preparing to break ground.

“It was a 15-year, 2-billion-billion dollar project, and everyone had already given their approval, including the Haitian government and the World Bank,” according to Gérald Emile “Aby” Brun, an architect, the president of NABATEC and vice president of the TECINA S.A. planning and construction firm.

“We can’t move them out… The idea is to reorganise the space so that people can live.”

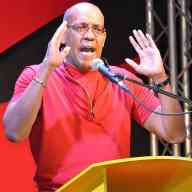

— Odnell David

A 2011 World Bank study of potential IEZ sites ranked it best out of 21 possibilities around the country, calling it potentially “high-performing” and “the clearest application of the IEZ concept among any proposed project in Haiti”.

MODEL CAMP LEADS TO DISASTER

Today, the plans have been shelved. The once empty landscape is now home to perhaps 100,000 people: 10,000 in the planned camps and the rest squatters. And they aren’t going anywhere.

“We can’t move them out,” Haitian government planner Odnell David told HGW in an exclusive interview. “The idea is to reorganise the space so that people can live.”

Urbanising about half of the wasteland will cost Haitian and foreign taxpayers “many hundreds of millions of dollars”, noted David, an architect and the director of the housing section of the government’s Construction of Housing and Public Buildings Agency. The price tag for initial infrastructure work already exceeds 50 million U.S. dollars.

Opened in April 2010 for earthquake victims evacuated from unsafe camps, the Corail-Cesselesse camp represented the reconstruction’s model resettlement. It sits on two sloping parcels of the 5,000 hectares of private land declared “of public utility” by the central government in March 2010.

But from the start, the choice to move people to the desert-like plain was controversial for two reasons.

First, some critics accused Brun and NABATEC of seeking to profit from the earthquake. Then, many said the land beneath the camps, and indeed much of the region itself, was not appropriate for settlement, whether temporary or permanent, for environmental and economic reasons.

Capitalising on Disaster?

Writing about the Corail-Cesselesse camp in an article and his recent book, Associated Press reporter Jonathan Katz accused NABATEC President Gérald Emile “Aby” Brun of pulling off a “backroom deal” by pushing the NABATEC land for emergency refugee camps so that he could eventually offer foreign companies “a ready-made workers community”. Brun was a member of a presidential commission that recommended the site.

Speaking to HGW, Brun did not deny that he had hoped the camps might one day be integrated into “a decent and modern housing scheme that had already been approved” as part of his firm’s “Habitat Haïti 2020” project.

But Brun also noted that the expanse of territory is the only open space left near Port-au-Prince, which is bordered on one side by mountains and a lake and by the Caribbean Sea on another.

“When they were looking for land for debris, land for recycling and eventually land for settlements, they realised that the state did not have any land larger than the size of a soccer field,” Brun said.

Brun – who resigned from the commission after Katz’s Jul. 12, 2010 article – said he never dreamed squatters would soon overrun the property.

“Why in the world would I have dropped a 14-year planning and investment dream and effort?” he asked.

Once the squatters began overtaking the area, foreign companies that had been negotiating with NABATEC dropped out of the project.

Despite the controversies, humanitarian agencies like the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), World Vision and American Refugee Committee (ARC) together spent over 10 million dollars to build about 1,500 small houses, schools, playgrounds, latrines and solar-powered street lamps.

Agencies had planned to build many more camps nearby, but as soon as the U.S. Army bulldozers cleared the first plots, tens of thousands of people invaded the surrounding area, “buying” parcels from racketeers, marking off plots and pitching makeshift tents.

No one in the central government said anything to prevent the incursions, which continue today. Many say the land was offered to supporters of President Préval’s “Inite” political party for 10 dollars per square metre.

The new “landowners” received fake titles in exchange for cash and their votes in the upcoming presidential elections, according to Brun and other sources, who asked not to be named.

Planned or not, and political scheme or not, today those tents have turned into houses built every which way, in what the UCLBP’s David calls a “savage urbanisation” with “no infrastructure, no water, no electricity, no sanitation”.

“People just appropriated land and are trying to accomplish their dreams of becoming homeowners,” he said.

NABATEC WANTS TO BE PAID

At first, Brun and NABATEC hoped the government and major reconstruction actors would eject the squatters and camp residents, or to at least turn the camp’s temporary shelters into permanent houses so that they could become the beginning of Habitat Haïti 2020 (see Capitalising on Disaster?).

But as months passed, the NABATEC partners – some of them members of Haiti’s most economically powerful families – realised their project would no longer be possible.

“The country lost a great opportunity,” Brun said. “I have been working on that project for 16 years.”

Now, NABATEC wants to be indemnified according to the law and the Constitution. The company has submitted paperwork to the government tax office and to each of the three ministers of finance who have held office since the “public utility” declaration.

If the government reimburses NABATEC for that land and the land currently occupied by the camps and the squatters, the company is due 64 million dollars.

“We have submitted all the papers and titles,” Brun said in May. “Verbally, in conversations, they say, ‘Yes, we recognise it’s your land,’ and they say they are going to pay us, but… nothing on paper.”

In an effort to confirm Brun’s statements, HGW made almost a dozen requests for interviews with tax office officials, in writing and in person, over the course of three months. Raymond Michel, head of the property division, promised an interview, but warned, “This dossier is very, very sensitive,” and later reneged on his promise.

Brun, meanwhile, is growing impatient. NABATEC is open to the idea of negotiating, but the company is also thinking about suing both the government and the humanitarian agencies that are continuing to carry out projects at Corail or are helping the squatters in the areas outside the camps, for “infringing on property owners rights”.

“It’s been three years now,” Brun said.

SEEKING FUNDING FROM, AND FOR, THE PROMISED LAND

While NABATEC lobbies the Ministry of Finance and the tax office for monetary compensation, the government’s Construction of Housing and Public Buildings Agency is also seeking funding, but not to pay the landowners. Instead, the agency hopes to carry out its own development: the urbanisation of about 500 hectares for the squatters.

According to David, an initial plan is ready.

“It is a very perfect plan. It has roads, it has water systems, it has sanitation,” David said, but he refused to share it with journalists, claiming it had not yet been approved.

But the proto-slum won’t turn into an organised neighbourhood any time soon. Among other challenges, the residents who have marked out “their” land will have to be convinced to move to make way for infrastructure.

“We will need a lot of resources, and the state doesn’t have all the funding it would need… We are seeking financing so that we can at least begin,” he said. “It won’t happen tomorrow.”

In the meantime, newcomers continue to arrive at the no man’s land with bundles of belongings, tent stakes and a few cement blocks.

Haiti Grassroots Watch is a partnership of AlterPresse, the Society of the Animation of Social Communication (SAKS), the Network of Women Community Radio Broadcasters (REFRAKA), community radio stations from the Association of Haitian Community Media and students from the Journalism Laboratory at the State University of Haiti.