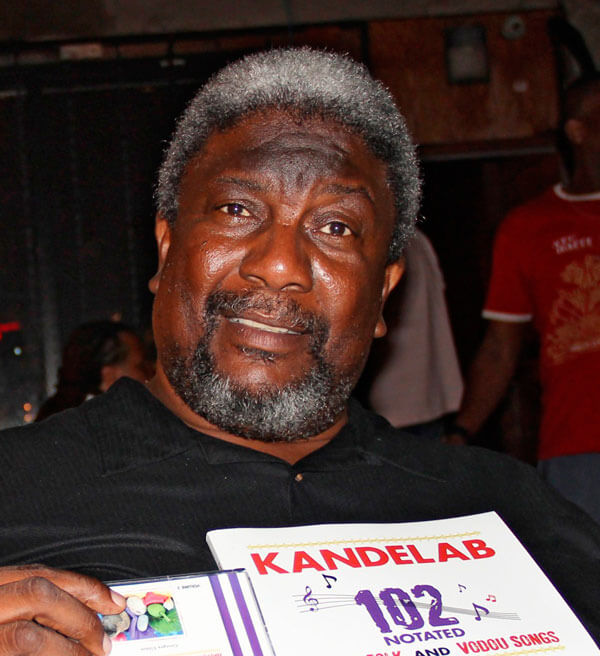

Georges Vilson’s passion is collecting Haiti traditional music and also the musical interludes that are part of some Haitian folktales. His passion is dedicated to acquiring the fabric of Haiti’s musical folk culture before it disappears.

The avocational folklorist went to parochial school in Port-au-Prince and his mother, who recently passed, was a church-going Catholic, but she had reverence for folk traditions.

“My mother was aware; she knew we must love the culture,” he says. “She was always singing traditional songs.” Though he didn’t grow up in the Vodou tradition, there was respect.

“Cousins from the countryside in the Nippes department visited us all the time and told us lots of stories,” he says of his own connection to traditional culture.

He elaborates that the role of the folktale is entertainment and education. “Most of the time there is a moral. They help you grow up.”

For the songs that are part of folktales, “It’s like a Broadway musical,” in this case, a very short song, part of the story as the teller spins the yarn. Integrated into the folktales and easy to catch on, listeners often sing along at the appropriate point.

“When I tell stories to kids, I always teach the song first,” he says, and the children take his lead to join in.

Vilson, affectionately known by his friends as Mous, makes research trips to Haiti during his vacations as a Brooklyn high school music teacher.

He never goes into a place without an introduction. A friend who might be a Vodou priest or mambo — a trusted reference — opens the door. Then, with a recording device in hand and accompanied with other friends, he’s ready.

On a recent visit to the Plateau Central, in the center of the country, he was in for a surprise. The chief storyteller greeted him, “We’ll talk about the stories, but we won’t tell them until the sun goes down.” Explaining, “It’s bad luck; we don’t want anything to happen to our family.”

With no accommodation arrangements, his group of four drove back to Port-au-Prince. “We returned the next week,” he said, having secured hotel reservations in a nearby city. And, recording all, the visiting group along with town folk listened from 6 – 10 pm. “I never knew stories aren’t told until the night,” he said, still learning the nuances of his cultural heritage.

In this second volume of 102 songs, 80 percent are Vodou or rara origin. The rhythms or dances are identified: petwo, chayopye, woumble, nago, kongo, yanvalou, and banda rhythms. Traditional songs make up the rest of the collection.

The music is notated, one song per page that looks like sheet music with the words printed.

Who uses the books? In addition to young musicians looking for the words or actual music of traditional songs, teachers in schools in Haiti use his book as a source. The size of the volume, with occasional full-page black and white photographs, is not bulky, a perfect carrying size.

Having amassed quite a few songs in 20 years of informally collecting, his research trips add to the archive. He sees himself, in total, notating 2000 songs.

The next and third traditional music volume in the Kandelab series — named for a thick many-branched cactus in Haiti that serves as a natural fence — will be “103 notated Haitian Folk and Vodou Songs.”

Accompanying the book and sold separately, Vilson recorded a set of CDs where he sings with a percussionist in Haitian kreyol, each song with its proper rhythm.

In the recording, sometimes you hear multiple voices or a choral background. “That’s me,” he says, of the multi-layered songs. The CD set also includes the songs played to a metronome on a piano, the notes from the sheet music slowly articulated. “It’s so people can follow along who don’t read music,” he says.

The Kandelab book or set of CDs can be purchased at Haiti Cultural Exchange’ s office, Five Myles Gallery, 558 St. Johns Place or on Amazon.