A glimmer of hope that reparations for African descendants whose ancestors suffered slavery has flashed across the European landscape with that continent’s parliament voting to address demands for compensation.

Members of the European Parliament voted in late March to recognise and make amends for several injustices — including slavery and the Atlantic Slave Trade — that were meted out and continue to be done to persons of African descent.

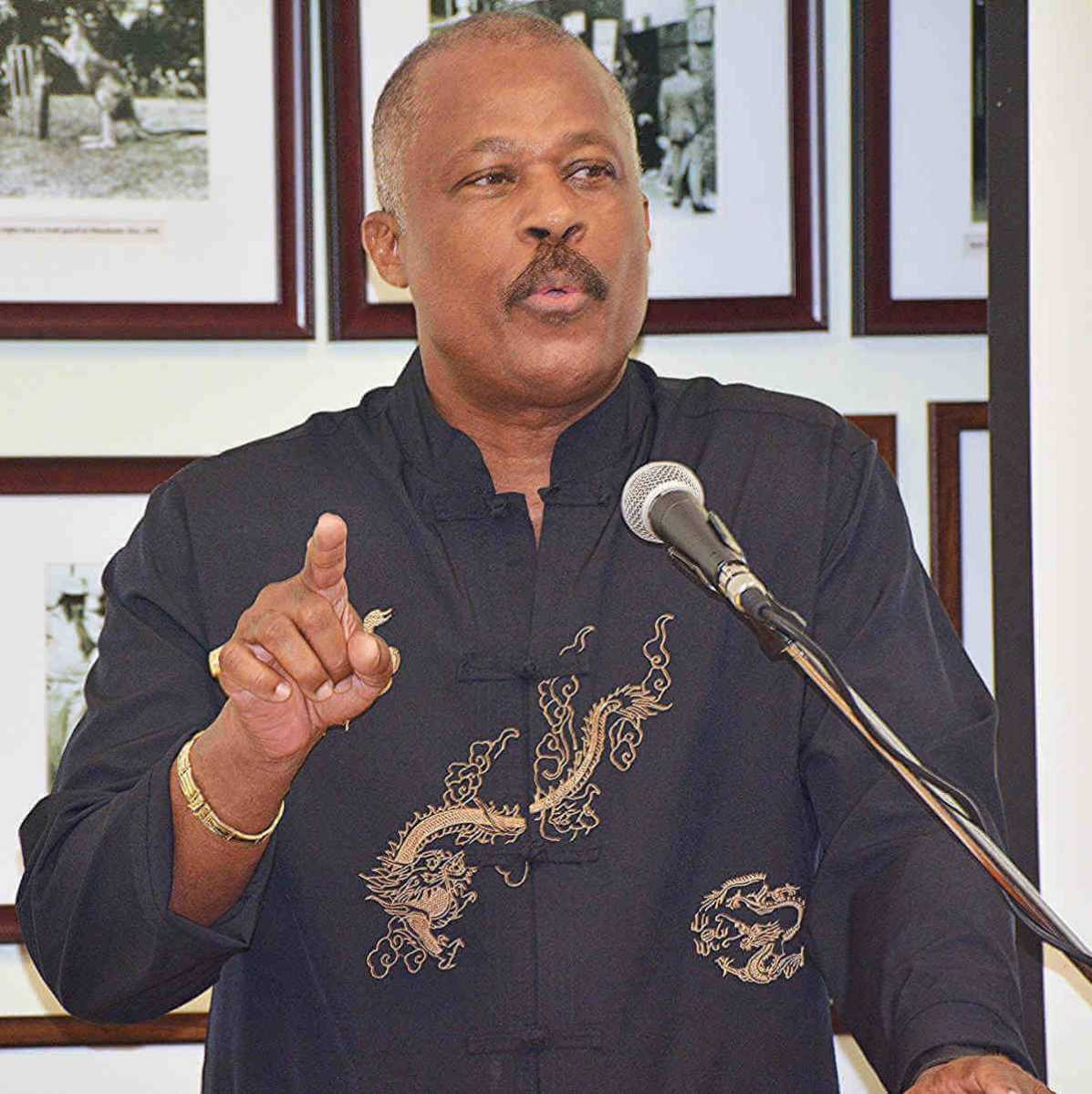

That vote by the law-making body for the whole of western Europe came within two weeks of University of the West Indies Vice-Chancellor, Hilary Beckles, imploring patience upon members of the African diaspora whose fore-parents were subjected to slavery.

Pointing out in early March that the call for reparations for some 300 years of forced and unpaid labour through slavery had been made long before slavery ended, he sought to convince offspring of those labourers who now live across the globe not to lose hope and continue the struggle.

Beckles had used examples of a likely hopeless state of mind of the enslaved, a little more than a decade before abolition of British slavery in 1833 and emancipation in 1838, who got liberation from an era that reached back to the early 16th Century.

“After 300 years of slavery, do you believe that your ancestors in 1820 thought they would ever see freedom… If you have been a slave for 300-400 years do you believe that anyone in that world could imagine freedom?” he asked rhetorically.

The professor then surmised, “if you had done a survey in 1820 among all the enslaved people of the Caribbean [asking]: ‘do you think freedom will come in your lifetime?’”

“I would venture to say that 90 percent of them would say ‘no, we will not see freedom in our lifetime.’

“But they did.”

Encouragingly he said, “some thing is going to happen in our lifetime that will trigger this conversation, because it is now taking place all over the world.

“The world is coming around to the realisation that a small number of people on the planet, the Europeans, used their military superiority to march into the continents of the world, destroy the societies and economies.”

Unknown to Beckles at the time of his speaking, a member of the European Parliament had already tabled a resolution for reversal of injustices suffered by Africans seeking to address, ‘fundamental rights of people of African descent in Europe.’

On March 26 those parliamentarians voted to encourage “the EU institutions and the Member States to officially acknowledge and mark the histories of people of African descent in Europe, including of past and ongoing injustices and crimes against humanity, such as slavery and the transatlantic slave trade, or those committed under European colonialism, as well as the vast achievements and positive contributions of people of African descent, through both the official recognition at EU and national level of the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade and through establishing Black History Months.”

This is among 28 points of call in the resolution, which was non-binding.

But with 535 MEPs voting in favour, 80 against and 44 abstentions passage of this agreement points to an overwhelming sentiment for corrective action by the 28 countries many who at some time engaged in the practice of slavery and the slave trade.

The press for reparations is against American and European governments that legalised slavery.

Beckles, a renowned historian who has authored over 21 books, including 17 on slavery and its effects on Third World societies and economies, had made clear that the reparations demand is not for cash but repayment through tangible developmental assistance for the centuries of forced labour that produced much of the wealth the modern world now enjoys, but for which the labourers were never compensated.