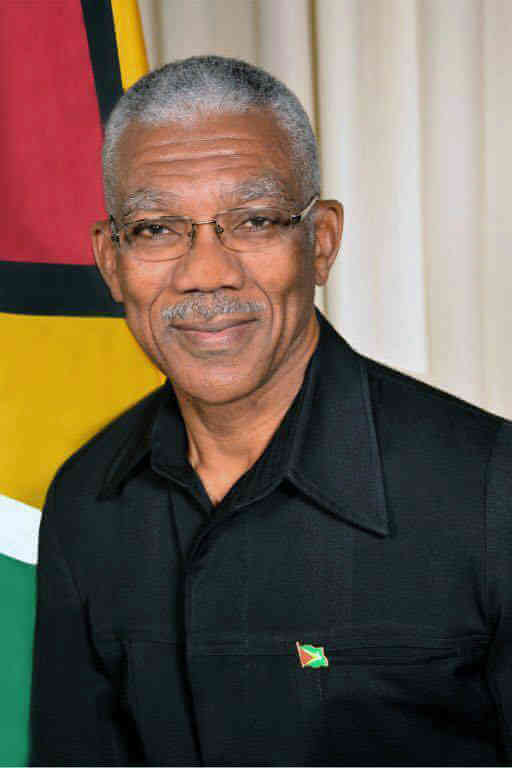

The Caribbean Community’s highest judicial body this week tried to make sense of Guyana’s unusual and highly complex electoral system, as its judges struggled to come to grips with aftermath issues linked to a late December opposition no confidence vote that had toppled the administration of retired army general David Granger.

At the center of issue is whether Parliamentary Speaker Barton Scotland erred on that historic night of Dec. 21, 2018 by agreeing that the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) only needed 33 votes to sink the multiparty governing coalition rather than 34 because the house is made up of 65 seats, an uneven number.

Therefore says, the coalition, one half of 65 is 32.5 and since there are no half humans, the number has to be rounded up to 33 and then one more shall be added to make it 34 for the vote to have carried.

So the team of high priced lawyers arguing the case before the Trinidad-based Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), Guyana’s highest and final court, that the judges must invalidate the pre-Christmas vote by agreeing that 34 votes or an absolute majority was all that was needed for the confidence vote to have carried. The PPP and its legal team contend that a simple majority of 33 votes were enough to topple.

Both sides have overwhelmed the four-person panel of judges with global precedents showing instances where the number was rounded up and added to 34 or sealed at 33, a simple majority, but the judges have at times during the three days of hearings asked for constitutional citations to back up the concept of an absolute rather than simple majority.

Additionally, the panel is also being asked to invalidate the vote of former government parliamentarian Charrandass Persaud who sided with the opposition to erase the administration’s wafer thing, one seat majority because he was not legally allowed to vote against his own parliamentary or electoral list.

Guyana’s electoral system is different form the others in the 15-nation Caribbean Community or single trading bloc as electors vote for a list rather than constituency or district representatives so loyalty to the list is paramount.

Government attorneys have insisted that Persaud’s vote was invalid because he should have obeyed rules which require him to inform his party and the speaker that he no longer supports the electoral or parliamentary list and would vote against it. Once that is signaled, he would have been recalled or scrubbed from the list even before voting. No other member state has such a complex or politically insipid rule so judges appeared to have been struggling to understand the Guyanese system. To do so, they have several times interrupted attorneys from both sides, the government’s in particular, to clarify constitutional points, concepts of conviction, ethics, political immorality and the rules governing parliamentary behavior as well as electoral practice.

Clearly perplexed by the Guyana system about bloc voting in the house, some of the judges wondered how it works in reality and how lawmakers could be kept in line by, for example, a chief whip or leader of the house.

“Is parliament a rubber stamp”? asked Justice Jacob Wit as lawyers detailed how the bloc, loyalty vote system is supposed to work.

Government attorney Neil Boston said Persaud, who fled to Canada on a Canadian passport after bringing down his own government, called Persaud a “usurper. He was in violation of the constitution,” as judges asked for supporting clauses to invalidate his vote. Persaud has been forced to deny accepting an opposition bribe of US$1 million even as police have launched an official investigation into whether he sold his vote and conscience.

In effect, the court is being asked to mediate in and solve a complex political issue that could have serious implications for the country as it readies itself to become one of the world’s newest oil producers from as early as November.

Senior attorneys say that as Guyana’s final arbiter is also expected to at least hand down several consequential orders, possibly giving a time frame for general elections and ordering some form of constitutional reforms to make electoral and parliamentary voting systems as less complex going forward.