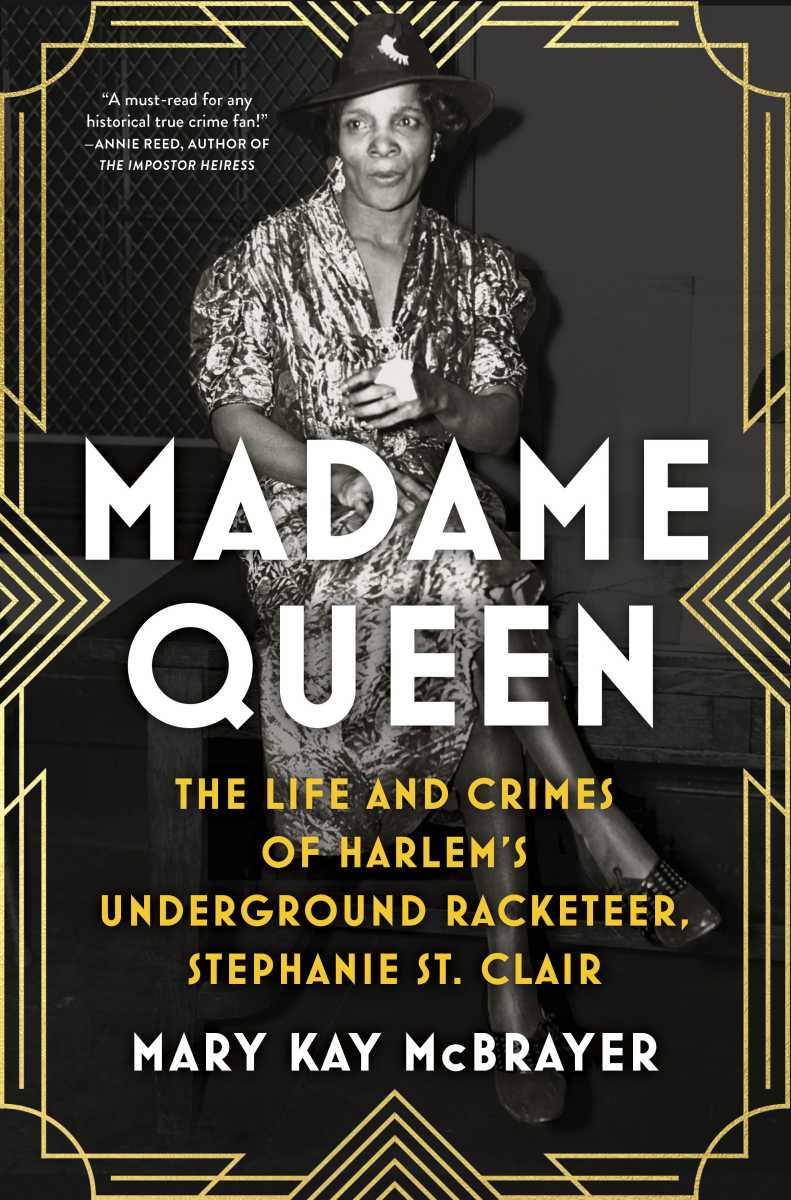

“Madame Queen: The Life and Crimes of Harlem’s Underground Racketeer, Stephanie St. Clair” by Mary Kay McBrayer

c.2025,

Park Row Books

$30.00

256 pages

Keep your eyes on the prize.

If you want something enough, you’ll never, ever lose sight of that goal. You’ll do what it takes to achieve it, letting it linger in your dreams at night and dictate where you live, who you live with, where you work, and what you do. Never look away, keep your eyes on the prize. As you’ll see in “Madame Queen” by Mary Kay McBrayer, it might be worth it.

It’s likely that young Stephanie St. Clair learned to lie from her mother.

Ancelin, says McBrayer, knew her daughter was “shrewd.” She probably figured that sending Stephanie alone on a ship from Guadalupe to New York was a chance for the girl to “spin straw into gold,” never mind that Stephanie was just thirteen years old. Still, it soon became obvious that Ancelin was correct: Stephanie took the ruse further and told a ship’s worker that she was twenty-three.

The year was 1911 and Stephanie arrived in New York, to a home for young female immigrants. McBrayer doesn’t believe that Stephanie made many friends there, but she kept her eyes open to opportunity, discovering at the White Rose Home for Colored Working Girls that she was good with numbers. There, she was also taught to sew, clean, save money, and how to comport herself as a lady.

Just beyond the doors of the home, she learned to shoot dice.

She was with a man who was courting her when she learned to play the numbers.

Though it’s a fact that she married George Gachette not long afterward, Stephanie never directly mentioned it anywhere, nor did she mention the child they had or the day she rented a room in Harlem and abruptly left them both. She took a job at a dress factory; later, she moonlighted at a bank, and began to plan.

From then on, says McBrayer, “She was investing in her own future…”

She was also building her own crime empire.

In her introduction, author Mary Kay McBrayer explains how this book came to be: she read something about Stephanie St. Clair and went in search for more but information was scarce. She admits that she inferred much and made up a lot to craft this story. She calls it “creative nonfiction,” and in “Madame Queen,” it works.

Such conjecture, in fact, actually works better because McBrayer serves as a kind of narrator in Stephanie’s story, filling in the many, many blanks with plausible conversations and likely facts that she backs up with sound reasoning. Indeed, the imaginary oozes between the truth to make this feel like a novel, but with occasional reminders that reality is somewhere, inside, outside, or nearby. It’s a tale told with fine sleuthing, dogged journalism, a well-described backdrop, and a touch of obvious admiration for its subject.

Readers who love biographies and can accept some speculation will devour this book, as will fans of historical novels, 1920s history, and The Sopranos. Look for “Madame Queen,” It’s a good surprise for the eyes.