The state of publishing in the Caribbean has regressed to the conditions of the 1940s, and apart from Barbados, anglophone Caribbean governments give short shrift to the literary arts.

So says Vincentian and leading Caribbean novelist and literary critic, Dr. Nigel Thomas, who while complimenting Barbados at a recent awards function for its vibrancy in promoting the arts, said the island has far to go for greater organisation in permanently recognising its outstanding artistes.

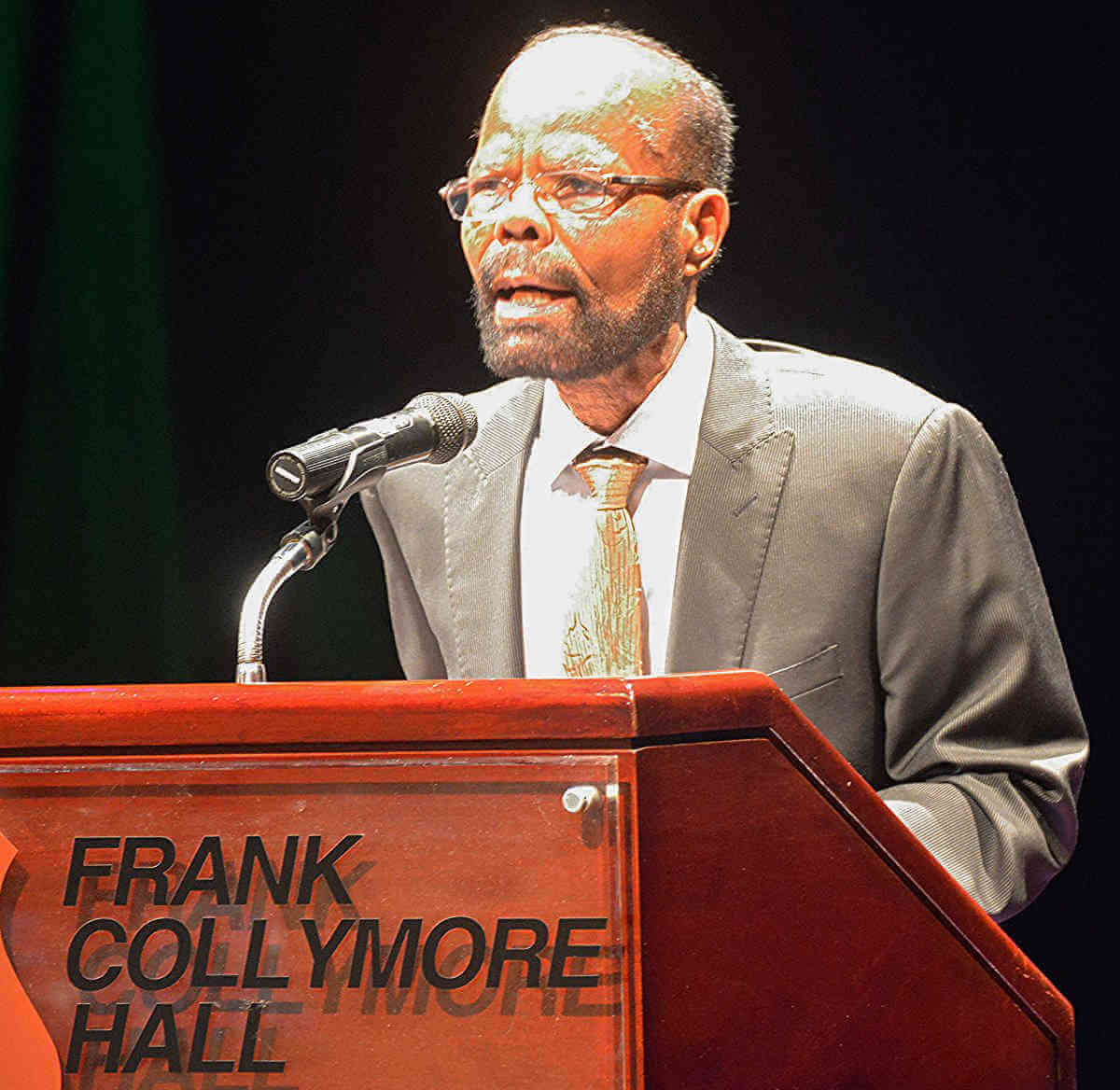

Speaking during the Frank Collymore Literary Endowment awards ceremony, Thomas gave kudos to the nation’s cultural administrators and Central Bank for leading the way for 22 years with this premiere writers’ recognition grant, but added, “I hope you will name something after [writers] Kamau Brathwaite, Austin Clarke, Cecil Foster, and eventually Robert Sandiford, and all those who come afterwards”.

Supporting his call for recognition of artistes he pointed to Canada where libraries, streets, and highways are named after writers. He spoke of a Hans Christian Andersen Boulevard in the centre of Copenhagen; and similar structures named for Victor Hugo in France and Martinique. Then there are in Russia Pushkin Squares, avenues and halls.

Thomas who lives in Quebec and is author of 11 books and five novels contends that the absence of recognition for creators in literary arts is part of a bigger problem in the English-speaking Caribbean where those who pen from their imagination have little or no publishing opportunities.

“Given the paucity of professional published Caribbean writers today we are back to where we were when Frank Collymore founded ‘Bim’ in the 1940s.

“I’m talking about writers published by presses that can promote their work and pay them royalties.”

Frank Collymore, a Barbadian poet, stage actor and painter, began publishing the literary magazine ‘Bim’ in 1942 providing for many Caribbean writers an outlet at a time when there was no other. He was editor until 1975.

Other publishers followed but they eventually packed up and left with the last significant one being Heinemann Caribbean Writers that departed around 1998.

“What I would like you folks in Barbados and elsewhere to do is to get after your governments,” he said.

“All the Caribbean countries have a department of culture and one would think that support for writers would be a major component. I can say that here in Barbados it is. In St. Vincent I know that it isn’t. There are some awards, but they are medals.”

Thomas argued, “our writers should not be facing such a bleak situation. Independent nations worthy of that name should offer greater opportunities and support to their writers.”

As an example of the fight to be taken to governments, he cited the Canadian situation 60 years ago when writers turned to US and UK publishers because none or few were available there.

“They organised,” he said of the Canadian writers. “The Canadian Council for the Arts was founded on a national level. Provincial arts councils, municipal arts councils all for the support the arts. Every single element of the arts.”

The result he said is that today a writer in Canada easily gets professionally published, “you’re invited to do readings. Your writer organisation has money to provide you an honorarium and pay your travel expenses.”

“Your books are present in public libraries. You are paid what’s called public lending rights.

“You are going to have to do the same thing. You are going to have to form those organisations and liaise with one another,” he told his mainly Barbadian audience.

“My hope is that the result would be that you could get some sort of regional publishing house that is funded by all the governments.”