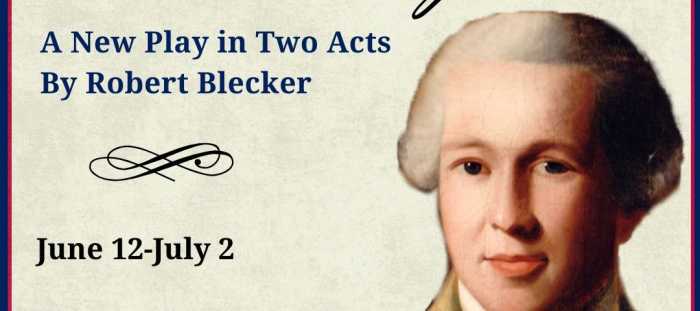

“The Firebrand and the First Lady” by Patricia Bell-Scott

c.2016, Alfred A. Knopf

$30.00 / $39.00 Canada

480 pages

You know your own mind.

After thinking things through, you have your opinions and while you’re willing to listen to what others say, you’re also willing to defend what you believe in. And, as in the new book “The Firebrand and the First Lady” by Patricia Bell-Scott, your friends don’t necessarily have to agree with you.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s Camp Tera, nestled near New York ’s Hudson River, was initially meant to be a temporary, leg-up place for Depression-era women who were destitute and totally without resources. Though she was young, educated, and married, Pauli Murray was there because of ill health.

Recovery-time aside, Murray’s tenure at Camp Tera was beneficial: a friend had told her that Roosevelt answered all correspondence, and Murray took that to heart. In 1938, a few years after she was kicked out of Camp Tera for “disrespecting the first lady,” she wrote a protest letter to Roosevelt, requesting intercession in FDR’s stance on anti-lynching laws. Activism was Murray’s passion and the answer she got wasn’t what she’d wanted but it did, as promised, come from Roosevelt .

Murray was born in 1910, the feisty granddaughter of a mulatto slave whose stories of injustice she grew up hearing. Murray lost her mother when she was just three; a few years later, her father was institutionalized, then murdered; and her brother was lobotomized. She, herself, had health problems and was often severely underweight; during one of her hospitalizations, she finally admitted that she was attracted to women, which was then considered to be a mental health issue.

It took awhile for Murray to tell Roosevelt all that. Before she did, and because of that first protest note, the two corresponded for years in letters that offered guidance, outrage, and rebuttal. The women didn’t always agree, but they always seemed to attempt to understand one another’s take on issues. Murray supported Roosevelt in her widowhood. Roosevelt encouraged Murray in her activism.

It was a support that Murray imagined she felt long after Mrs. Roosevelt’s death.

I would not, under the broadest of terms, call “The Firebrand and the First Lady” a pleasure read.

That’s not to say that this book isn’t a pleasure — it’s just not something you’d pick up to relax with. Author Patricia Bell-Scott goes deep into the politics and work of both Roosevelt and Murray (more the latter than the former) and that can be very dry. It’s informative — Bell-Scott tells a story that’s been largely hidden for decades, about a woman who left her mark on social issues in many ways — but it’s far from lively. Adding more details of Murray’s personal life might’ve helped; that’s what I was hungriest for, but didn’t get enough of.

I think this is an important work of history and definitely worth reading but you’ll want to be in the mood for it, particularly if you usually like lots of energy in your stories. If you’re a scholar or historian reading “The Firebrand and the First Lady,” though, the pace is something you probably won’t mind.